Fear Beyond the Fence: Defending local livestock

In portions of Minnesota and Wisconsin, farmers have struggled to protect their livestock from wolves.

“I don’t think I know any farmers that haven’t had some kind of run in with the wolves, some more than others,” said livestock farmer Dustin Soyring. “I’m constantly worrying about the safety of them and if I’m going to lose one of them.”

Livestock has been part of the Soyring family farm for around 120 years. Soyring said that the first time the farm had issues was in 2006.

“Then it was kind of on and off again for a few years, but in the last probably ten years it has been a constant battle of problems and different issues arising with the wolves in the area,” said Soyring.

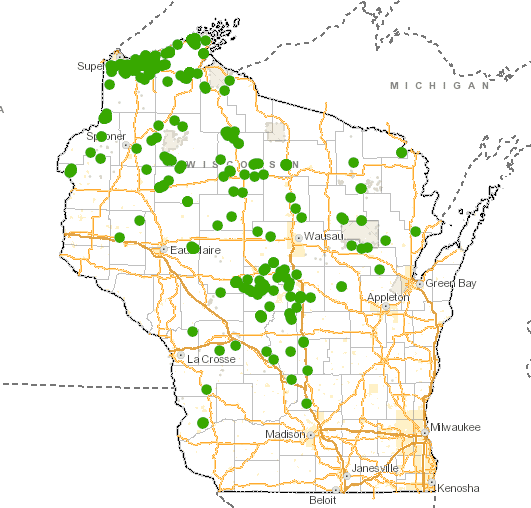

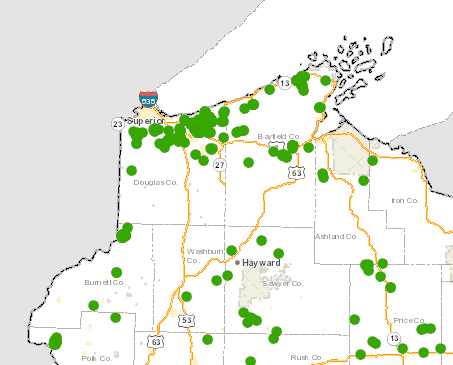

The Soyring farm is in Maple, Wisconsin, which seems to be a hotspot for livestock predation. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Wildlife Damage Specialist Brad Koele says that in 2023, the DNR received 115 complaints about wolves attacking livestock.

“80 of those were verified to be caused by wolves,” said Koele. “Majority of our complaints, however, do come from the northern part of the state, particularly if you’re looking at livestock conflicts. You know, up in the Douglas County area, northwest Wisconsin. In many cases, it is the same pack. It’s kind of a learned behavior where the parents or the mother teaches the pups to prey on livestock. So it’s kind of a learned behavior, and often the same packs that are involved in the conflicts.”

For Soyring Farms, the number of calves killed by wolves varies by year. Soyring says the highest number was 26 calves either confirmed killed or missing in one year. Last year, there were five confirmed kills and a total of 11 missing on the farm. Even calves not attacked can be impacted by wolves being near the farm.

“It causes a lot of stress to the cows. They don’t grow as well. They become nervous,” said Soyring. “I estimated this year all my cows were 50 to 100 pounds lighter than what they should have been, and they’ve done studies that prove that the wolf stress on cattle causes a lack in growth. At the end of the day, that can cost me $15-20000 for the amount of animals that we sell.”

One example of a study that was done was from University of Montana faculty and staff in 2014.

The abstract states, “ranches that experienced a confirmed cattle depredation by wolves had a negative and statistically significant impact of approximately 22 pounds on the average calf weight across their herd, possibly due to inefficient foraging behavior or stress to mother cows.”

When a farmer has an issue with wolf depredation, the claim is investigated by the DNR and the USDA. Investigations are usually done the same day the complaint is received to ensure evidence is more fresh. Doing so aids in making an accurate determination as to the cause of death, including the determination of whether a calf was killed by a coyote, a bear, or a wolf.

“They all have different signatures on how they kill prey or domestic animals, so we’re looking for evidence like tracks, scat,” said USDA Wildlife Biologist David Ruid. “We look for bite marks in key locations on the carcass where we can measure the distance between the canine teeth. We’re also looking for bruising and hemorrhaging, indicating that when that carnivore bit that livestock animal, it was alive. “

For farms with confirmed wolf depredation, the USDA and the DNR work alongside farmers to scare wolves away from cattle. Methods include fladry, flashing lights, and playing radios at random to make it seem like humans are nearby.

“The flags, they get used to that and several months later they’re going underneath the flags. The lights didn’t seem to bother them after about a month or two, and the radios work well for a short period of time. We’ve seen it where the wolves are actually chasing the cows while the radio is on within a hundred yards of the radio,” explained Soyring.

The aforementioned methods can be ineffective for preventing wolves from deprecating livestock. So far, the only nonlethal tool that seems to stay effective is a wolf-proof fence. Six chronic farms, including Soyring Farms, have had fences put up by the DNR and USDA using grant funding from congressional appropriation received several years ago.

Each fence is six feet tall with high woven wire and wire skirt underground to keep wolves from digging under. Between the limited funding and the features of these fences, they cannot be put just anywhere.

“It’s in the neighborhood of 8 to $9 a linear foot to build one of these fences,” explained Ruid. “And then you have to have the right site. We don’t have the funding to fence every producer that’s having wolf conflict. So every year we do an evaluation on who’s having the worst conflicts where they’re at, and we do a site assessment to look at the feasibility of actually constructing a fence. Then the farmer/rancher, they’re responsible for site preparation.”

Soyring plans on using the newly fenced-in portion of his farm as the birthplace of calves so that the cows can have calves safely and remain away from wolves while the calves are young.

“I feel very confident about this fence. I’m actually extremely excited when we were able to get this put in,” said Soyring. “We left it open for a while and we had lots of wolf tracks outside, and we never had one on the inside.”

While the cows in the fenced area of the farm are safe for now, there are still wolves in the area that could begin hunting at nearby farms. Wolves have been around northern Wisconsin since the mid-1980s, but tracking them has been a challenge.

“Every winter we have a volunteer tracking program where we have a number of survey tracking blocks throughout the state and try to determine the number of individual wolves. We have a number of wolves that are collared, so our DNR pilots will fly around in the winter, locate those wolves, and then count the number of individuals within that park,” said Ruid. “Population here has been pretty stable. Anywhere from 1000 to 1200 wolves seems to be our over winter count. I do want to stress that it is over winter count, and that’s certainly at a point where the wolf population is at its lowest level.”

Even though they continue to cause problems for farmers in northwest Wisconsin, population control methods are limited.

“To control the wolf population, there’s not much we can do at this point in time. In Minnesota, they are a threatened species. In Wisconsin, they are an endangered species,” said Koele. “So what that means is in Wisconsin, we don’t have the ability for any harvest season and we don’t have the ability to implement any lethal control in response to conflicts, whereas under the threatened status, you know, there’s ability to implement lethal control at conflict sites.”

Many are pushing for delisting wolves from the federal endangered species list.

RELATED: Are wolves to blame for the deer decline?

“DNR supports an integrated conflict program. You know, and that includes both lethal and non-lethal controls, you know, So there’s not much we can do about that until we get a de-listing,” said Koele.

The USDA also supports adjusting the listing status.

“Until they’re reclassified, either threatened or delisted, we’re not going to have that full set of tools to deal with these conflicts. As hard as we try with non-lethal abatement, just other than having an employee camp with the cattle at night or putting a fence around them, you know, these traditional tools will become ineffective,” said Ruid. “Given the density of livestock in an area you could protect one farmer’s animals and ultimately shift the issue to another livestock producer.”

Soyring supports delisting wolves as well to help not only his farm but also others in the area.

“I understand that the wolves were natural to this area, but I think that the management needs to be done a little bit better to help accommodate farmers and people,” said Soyring. I mean, the area and times have changed and it’s a lot harder to cohabitate with the amount of wolves that are in the area.”

The Wisconsin DNR map of gray wolf depredation on livestock, hunting dogs, and pets can be found at this link. Tips on reducing conflict with wolves can be found at this link.