Lake Adney: A sanctuary to African Americans for nearly 100 years

[anvplayer video=”5163230″ station=”998130″]

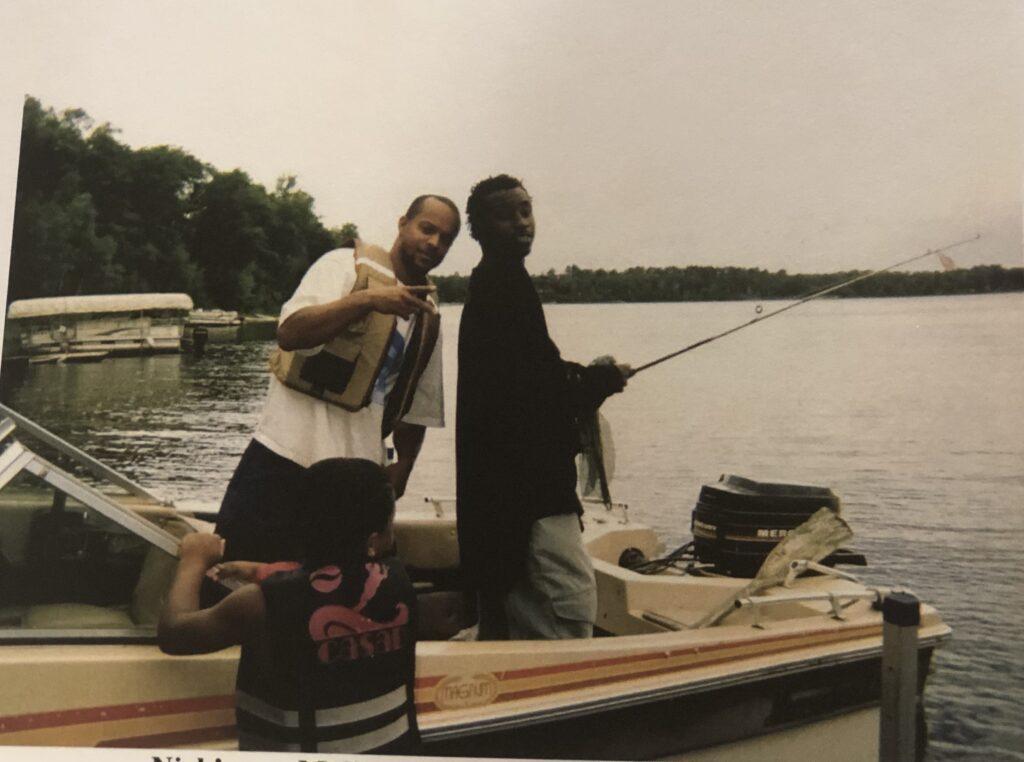

In Minnesota, going up North for the weekend to experience cabin life is no rarity. Something good is always cooking up North—family time, fishing, exploring, or just simply enjoying the lake views. However, for the last century a lake in Crow Wing County, Minnesota has done more than that. It is called, Lake Adney, and for nearly 100 years African Americans from all over the country have come there to have their own piece of paradise.

“A community mailman, I would see him off and on and ask him, how are you doing? He’d say, I’m doing great. And I’d ask, what you’ve been up to, he’d say he’d been up to paradise. And he would always make reference to paradise, and then I’d ask him a little bit about paradise. He told me about the lake, a little bit about the history of the lake and I said, well you know, we would like to maybe check that out some day,” says Nathaniel Khaliq. Khaliq was president of the St. Paul NAACP for fifteen years until he retired in 2011. He and his wife, Victoria Davis, purchased property on Lake Adney in the 1980s.

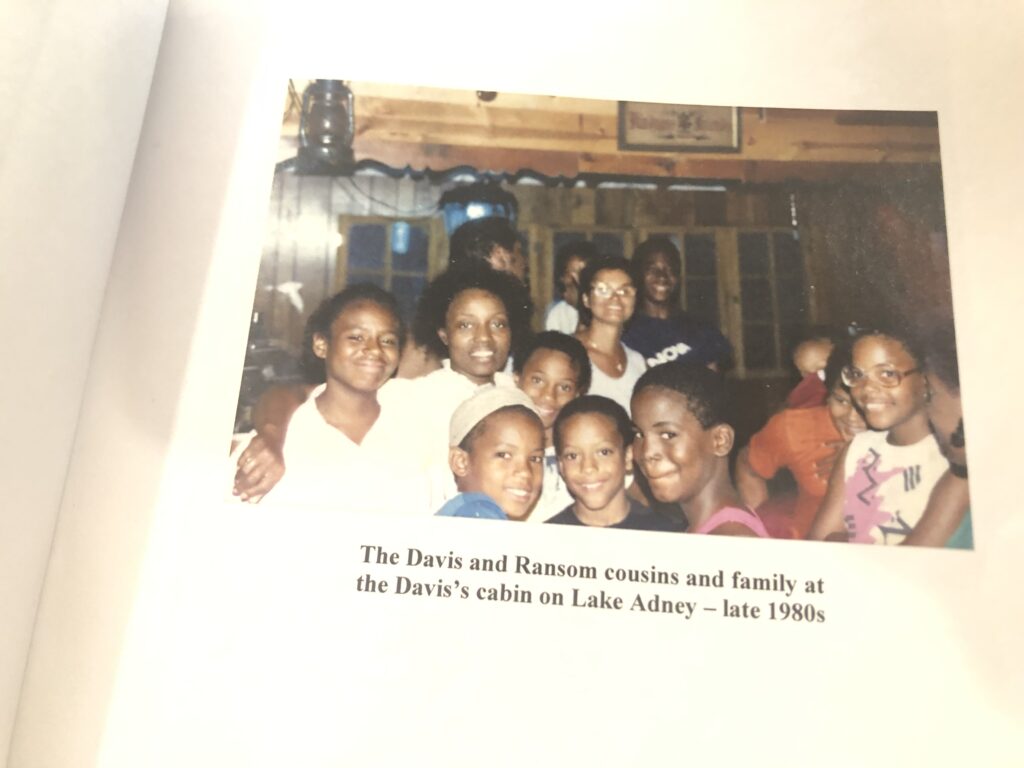

According to Khaliq, during that time period in the 80’s, about 80% of the people living on their side of Lake Adney were black.

“Haven. That was the name of this cabin. And so I just think it was an opportunity for folks to get away from the racism, the discrimination, the stress that some of them were dealing with and generational trauma and so forth. And then to come up here and to be able to spend that time and enjoy yourself with people that cared about you,” continues Khaliq.

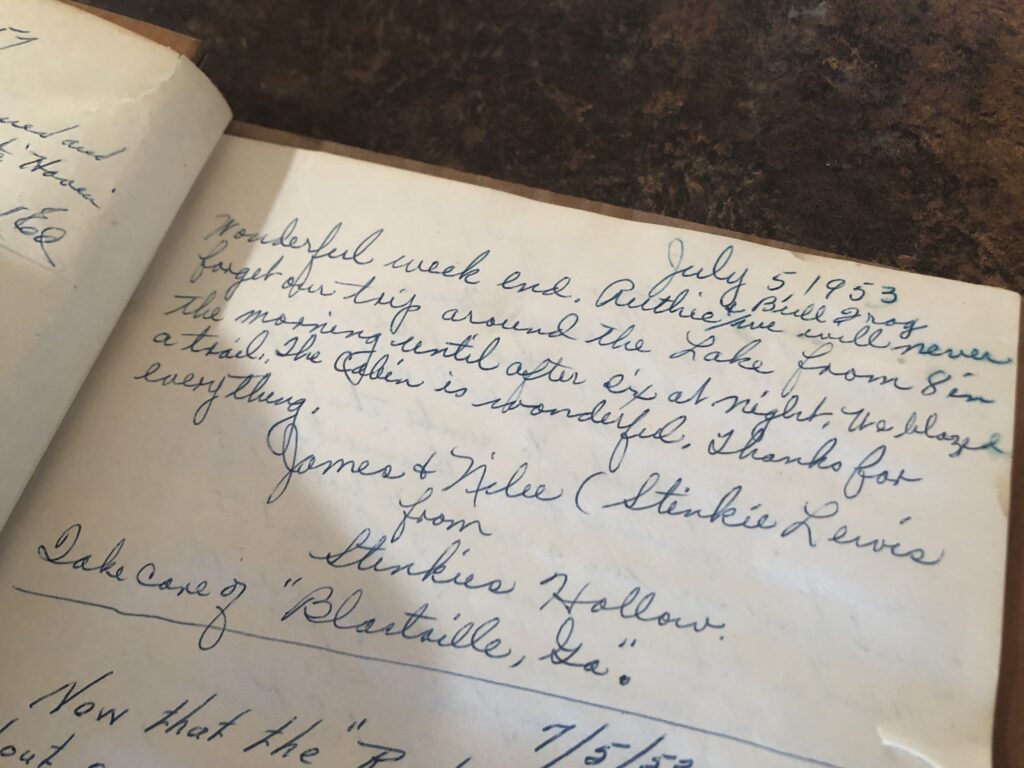

As you walk around Khaliq and Davis’s cabin, it is a portal in time. Mementos from the past align the walls and fill the cabinets everywhere. Anything from ornaments, to paintings, to furniture, an absolute testament to the preservation of history.

“History means so much to me because both my grandparents on my mother’s side were born during slavery and my mother was always a very thrifty person. We had chickens in our back yard, so she would go grab a chicken and she would ring its neck and eat it for dinner… and we picked the feathers off, and she had a bag, where she stored feathers in it. She gets enough that she would make a pillow… She got some feathers; she’d make the mattress. So, I was brought up knowing that you value everything…” says Davis, a teacher who founded a children’s program in St. Paul for youth that had trouble reading and writing.

Philip Mitchell is a current resident on Lake Adney and lives there full time, he is the third generation in his family to take over the cabin.

“There were a few people that knew about this area up north and were trying to get people to come up here and just kind of relax and go fishing and have a good time. Eventually that turned into, we really like it up here. Or maybe we should buy a place and some of those close, close friends of my grandfathers, all of them bought property at one time or another on this lake. I feel very fortunate to have had parents and grandparents who had the foresight to see something that they really enjoyed and put the hard work in to get it to where we are now,” says Mitchell.

According to records, at one time cabins on Lake Adney were owned by African Americans not only from Minneapolis and St. Paul, but also Omaha as well as Chicago. In addition, a handful of black owned resorts in the area drew vacationers from places as far and wide as New York and California all by word of mouth.

Lake Adney, Crow Wing county Minnesota

However, the properties and ownership along Lake Adney have changed quite a bit as the decades have rolled by. There are fewer and fewer black cabin owners along its shores than decades ago.

“I got a one in three chance that my kids and my grandkids and my grand puppies will settle down here on weekends and hang out and then go home for a while and then maybe somebody will end up living up here again,” says Mitchell.

However even with the declining numbers of black families in Lake Adney, the legacy still prevails.

“When we talk about the legacy, you know, we’re tying in something that’s bigger than us. You know, we’re talking about being able to participate in the world and all the beautiful things we get to participate in. We take our flag, you know, going back to find a place, you stake your flag in the ground. That’s mine. That’s ours… so I mean, it’s too much pride and family and memories,” says Malik Davis, a firefighter in the Twin Cities and the son of Nathaniel Khaliq and Victoria Davis.

“I want to commend and honor those that are not with us anymore but made a special effort when they got ready to sell their place. They said, I want to sell it to somebody in the community. And some did that, and some did not. But just the fact that even if they took a little less money, they wanted to make sure that our legacy as the people here in Minnesota and in the Twin Cities would go on forever,” finishes Khaliq.

Lake Adney is a hidden gem up North full of history and legacy that is unimaginable. You walk on its grounds and there is a sweet silence that enters through every pore, until you’re not the same person who originally walked on the land. It truly is a piece of paradise. To learn more about Lake Adney, The Minnesota Historical Society has gathered oral histories of some of the African American cabin owners. You can listen to them by clicking here: http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/oh178.xml